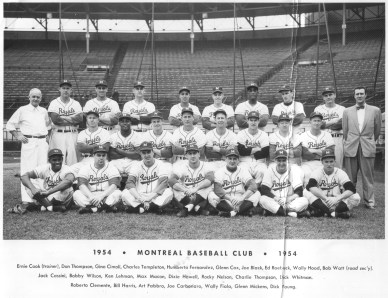

Former Montreal Royals manager Max Macon could never escape the questions about Roberto Clemente.

Was he or was he not part of a conspiracy to try to hide the talents of Clemente in 1954?

To provide some background, when Clemente was signed to a $15,000 contract by the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1954, the big league club took a significant risk when they assigned him to the Royals. At that time, there was a rule in place that stipulated that any team signing a rookie to a contract over $4,000 must keep that player on their major league roster for the season or risk losing him in a post-season draft.

Clemente’s 1954 campaign with the Royals wasn’t particularly memorable. Despite being one of the Dodgers’ best prospects, the slender outfielder was sent to the plate only 148 times in a 154-game season. His lack of playing time was puzzling – a trend that began in the Royals’ home opener, when after registering three hits in four at bats, he found himself on the bench for the next game. Even belting a monstrous home run that cleared the left field wall and went right out of Delorimier Stadium (the first player to accomplish this) wasn’t enough to earn him a regular spot in the lineup.

“The evidence seems to indicate that the Dodgers were trying to hide him,” Bruce Markusen, author of “The Great One,” an excellent book about Clemente, told me in a 2002 interview. “I mean if you have a young player with that much talent and you’re trying to develop him, you don’t limit him to 148 at bats.”

In his book, Markusen also notes that during Clemente’s tenure with the Royals, the future Pirates star often took batting practice with the pitchers and would typically only play the second game of a double-header (most scouts from visiting teams would leave after the first game). These tactics seemed to support the theory that he was being hidden.

But if Clemente was, in fact, being hidden, the Pittsburgh Pirates were not fooled. Branch Rickey, then the general manager of the last-place Pirates, dispatched scout Clyde Sukeforth to check out Royals pitcher Joe Black. Legend has it that the veteran scout grew so enamored with Clemente that he never did see Black pitch. Before the end of his trip, Sukeforth had his mind set that the skilled outfielder would be the Pirates’ number one pick in the off-season draft. The rest, as they say, is history.

For his part, Macon denied that he was under any instructions from the Dodgers to “hide” Clemente.

“I never had any orders not to play Clemente,” Macon would tell the Reading Eagle for a story published on November 25, 1971. “I was told Roberto was only 18 when actually he was 19, but I had three proven Triple-A outfielders in Sandy Amoros, Gino Cimoli and Dick Whitman. When the Dodgers took Amoros to Brooklyn, I had Jack Cassini and Don Thompson. I was told to win at Montreal and simply had to play more experienced men. Roberto got in 87 games and I think that’s good for a rookie.”

Macon added that Clemente’s skills were also still raw.

“To me, Roberto was a fill-in guy, an enthusiastic rookie, you spot in a game without rushing him,” said Macon. “Amoros and Whitman didn’t have the strongest arms in the world and if we were leading late in the game I would take them out and put Clemente in for defensive purposes. He always did the job.”

Understandably, Clemente was not happy with his lack of playing time.

“I was confused and almost mad enough to go home,” Clemente once said about his 1954 season with the Royals (as reported in William Brown’s “Baseball’s Fabulous Montreal Royals”).

The young Puerto Rican prospect also believed that Macon didn’t like him, an allegation that the ex-skipper disputed in that 1971 story.

“There was little doubt of his potential, but his growing up came along later,” said Macon. “He put things together to become a star. Nobody could be more delighted about his career than I.”

With Clemente in a support role, Macon led the Royals to a 88-66 record in 1954 and within one game of a league championship. It would be his only season as the manager of the Royals. Following that campaign, Macon was re-assigned to the Dodgers’ other Triple-A affiliate in St. Paul, where he was the dugout boss for five seasons from 1955 to 1959. He finished his managerial career with stints in the Reds and Tigers organizations in the early ’60s, before becoming a scout.

Prior to his career as a skipper, Macon was a multi-talented player. Born in Pensacola, Fla., in 1915, he was signed by the St. Louis Cardinals as a pitcher in 1934. He won 15 games for the Cards’ Class-C affiliate in Hutchinson that year to begin his ascent through the Cardinals’ minor league ranks, which culminated in him winning 21 games for Double-A Columbus in 1937. Along the way, Macon also proved he was no slouch with the bat. On top of registering 21 victories in 1937, he also hit .357.

The 6-foot-3 southpaw made his big league debut with the Cardinals in 1938 and posted a 4-11 record and a 4.73 ERA in 38 appearances. He also registered 11 hits in 36 at bats for a .306 batting average. He returned to the minors in 1939 to toe the rubber in Double-A for Newark and Columbus, before he was purchased by the Dodgers on September 2, 1939.

Macon spent the bulk of the four ensuing campaigns pitching in Triple-A with Montreal. During those seasons, he was shuttled between the Royals and the Dodgers. His finest big league stretch came in 1942 when he posted a 1.93 ERA in 14 appearances and also hit .279.

On November 2, 1943, he was selected by the Boston Braves in the Rule 5 draft. The following season he became the Braves’ regular first baseman and suited up in a career-high 106 big league games.

His baseball career was disrupted by military service in 1945 and 1946. He served in the U.S. army, first at a base in Fort McClelland, Ala., and then in Fort Meade, Md., starting in April 1945.

Macon returned to the Braves in 1947 and played his final big league game. The Florida native would then embark on a series of minor league player/manager gigs – his most successful coming with the Class-D Hazard Bombers of the Mountain States League in 1951. On top of leading his squad to a 93-33 record and a league title, Macon hit .409 and knocked in 148 runs, and was also 4-0 with a 1.20 ERA in seven pitching appearances.

Macon continued as a minor league manager until 1963, before becoming a scout. While he worked as a scout, he was reportedly stationed in Louisville, Ky., where he also became a high school and college basketball referee. He moved back to Florida in 1966.

Macon passed away on August 5, 1989 in Jupiter, Fla.

*This is the 14th article in my series about members of the 1954 Montreal Royals. You can read my articles about Roberto Clemente, Billy Harris, Don Thompson, Gino Cimoli,Chico Fernandez, Glenn Cox , Joe Black, Ed Roebuck, Jack Cassini , Bobby Wilson, Ken Lehman, Charlie Thompson and Dick Whitman by clicking on their names.

By coincidence, I am currently halfway through reading a book called “Clemente” by David Maraniss, published in 2006, which I think is worth reading. Early on in the book, he writes “Max Macon, the manager, denied that he was being told whom to play, but few took that claim at face value. Glenn Cox, a pitcher on the team, said players always know about other players, and it was obvious to all of them that Clemente was something special and deserved more time. ‘Macon had orders, and that was that,’ said Bob Watt, who served as road secretary for the Royals. ‘Whenever we’d spot a scout in the stands, that would be the end of Clemente for that day. He never had a chance to show what he could do.’ The thinking in Brooklyn, Buzzie Bavasi acknowledged later, went like this: ‘Since we were going to lose him anyhow in the draft, why would we spend so much time developing him for someone else? We used other players and Clemente went in only on defense in the late innings or played sparingly.’ “

Thanks for adding this, Len. I did read the Maraniss book a few years ago and forgot about that passage. It’s a wonderful book. Thanks for adding valuable information to my blog entry.

a great story…what a tough job he had to do with dealing with Clemente.

Thanks for the comment, Scott.